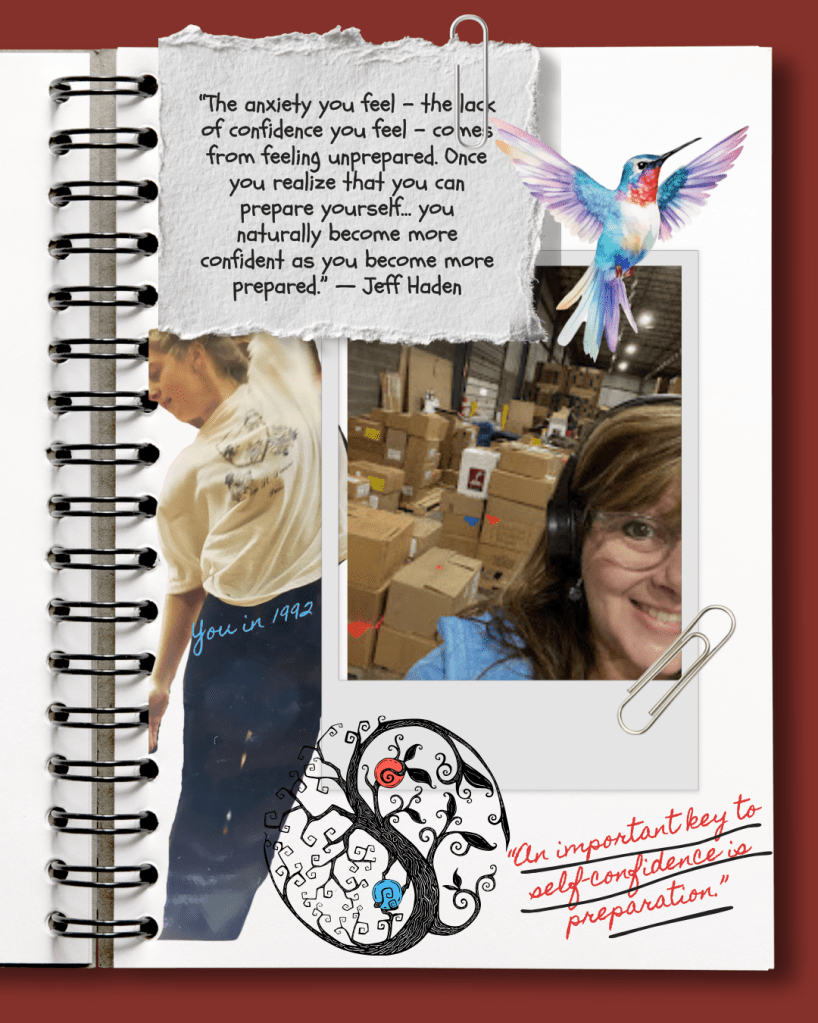

The Buckeye Book Fair is nearly here. Soon, hundreds of authors and thousands of readers will gather in celebration of books and stories. Yet few realize the sheer scope of the behind-the-scenes work. My role is to move and manage more than seven thousand books. That responsibility alone is enough to trigger professional anxiety. The logistics, the timelines, and the possibility of mistakes can feel paralyzing. Over the years, I have discovered that the best way to navigate professional anxiety is through practices that build self-confidence: visualization, reflection, and planning. These are not abstract ideals. They are disciplined approaches that help leaders balance responsibility with resilience.

Visualization with Partners

Anxiety often grows in the gaps between preparation and execution. One way to close those gaps is through intentional visualization. Just as performing artists rehearse before stepping onto the stage, leaders must imagine conversations, questions, and outcomes before walking into meetings with stakeholders. This process not only reduces anxiety but also strengthens alignment with organizational values.

Research shows that even in the technical realm of grant writing, language shapes credibility and trust between nonprofits and funders. Visualization allows leaders to anticipate how values and needs will be expressed, thereby fostering authentic communication with partners. Without such preparation, leaders risk bending their priorities to meet funder expectations, creating dissonance between organizational identity and external demands. That dissonance, in turn, fuels professional anxiety. With visualization, leaders instead approach partners as confident collaborators who can articulate both budgetary detail and mission integrity.

Professional anxiety comes from responsibility and logistics, not stage fright.

Visualization with partners builds confidence and prevents misalignment of values.

Reflection with colleagues strengthens emotional intelligence and reduces isolation.

Planning with clients/audiences channels unpredictable energy into productive outcomes.

Balancing confidence and vulnerability keeps anxiety manageable and growth-oriented.

Reflection with Colleagues

Isolation intensifies anxiety. Leaders, like performing artists, can become so consumed with tasks that they neglect meaningful relationships with colleagues. Creating time for reflection—both alone and with others—fosters resilience and cultivates emotional intelligence.

Research demonstrates that emotional intelligence is not only a predictor of communication effectiveness but also a buffer against anxiety in professional settings. Fall, Kelly, MacDonald, Primm, and Holmes (2013) highlight its role in reducing intercultural communication apprehension, a finding that extends to workplace interactions across diverse contexts. Furthermore, Mattingly and Kraiger’s (2018) meta-analysis suggests that emotional intelligence can indeed be developed through training and practice. Reflection with colleagues provides one such training ground.

For leaders, making space to debrief with coworkers before and after major projects encourages social competence and builds trust. When anxiety is shared in dialogue rather than carried in silence, it becomes manageable. In my own work, discussing challenges with my team transforms a daunting task like transporting seven thousand books from an isolating burden into a collaborative achievement.

Photo: Kimberly Jarvis and David Wiesenberg meet up to exchange decades of Buckeye Book Fair strategies.

Planning with Clients and Audiences

Clients, patrons, and audiences bring unpredictable dynamics to any endeavor. Their enthusiasm can inspire, but without planning, it can also overwhelm. Leaders who prepare thoughtfully for these interactions are better equipped to guide energy and expectations.

The arts illustrate this dynamic vividly. Wolfe (2012) describes how audience reactions to child beauty pageants both sustained and reshaped the industry, creating awareness of troubling practices even while driving viewership. The lesson extends beyond the arts: audiences wield power, and their responses can shift the trajectory of work. For leaders, anxiety arises when audience influence feels uncontained. Planning provides the boundaries that turn uncertainty into strategic engagement.

Including clients or audiences in the process is not a weakness but a strength. It creates opportunities to adapt, build loyalty, and channel passion in productive ways. With careful planning, leaders gain the self-confidence to manage unpredictable responses without being destabilized by them.

Balancing Confidence and Vulnerability

Professional anxiety is not eliminated by experience. New responsibilities, higher stakes, and shifting contexts ensure that anxiety continues to surface. The question is not whether leaders will feel anxious but how they will respond.

Visualization, reflection, and planning are disciplines that build confidence and resilience. They transform anxiety from a paralyzing force into a manageable companion. Yet it is also essential to acknowledge vulnerability. Leaders who admit challenges, seek support, and remain open to growth model a sustainable way forward. Professional anxiety, when approached with both discipline and humility, becomes part of the learning process rather than an obstacle to it.

The Buckeye Book Fair will soon fill the room with readers and authors, and behind it all stands the work of moving seven thousand books. That number still brings a knot to my stomach, but I know how to face it. By visualizing with partners, reflecting with colleagues, and planning with clients and audiences, I move through the anxiety instead of being held back by it. Professional anxiety is real, but it need not be paralyzing. With preparation and confidence, it becomes part of the rhythm of leadership—challenging, yes, but ultimately carrying us toward the very outcomes we most value.

Storage of boxes during the Buckeye Book Fair, 2023

References

Connor, U., & Wagner, L. (1998). Language use in grant proposals by nonprofits: Spanish and English. New Directions for Philanthropic Fundraising, 1998(22), 59–74.

Fall, L. T., Kelly, S., MacDonald, P., Primm, C., & Holmes, W. (2013). Intercultural communication apprehension and emotional intelligence in higher education: Preparing business students for career success. Business Communication Quarterly, 76(4), 412–426.

Mattingly, V., & Kraiger, K. (2018). Can emotional intelligence be trained? A meta-analytical investigation. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 164–178.

Wolfe, L. (2012). Darling divas or damaged daughters? The dark side of child beauty pageants and an administrative law solution. Tulane Law Review, 87(2), 427–455.

Leave a comment